Author: Michelle, RD. For reprint permission, please provide the source

Hello friends! Today, I want to share the story of an elderly friend with type 2 diabetes, diagnosed 18 years ago, who achieved diabetes remission within six months, and some dietary strategies that might help us restore β-cell function. As a certified nutritionist with practical experience, my team and I have witnessed many friends with type 2 diabetes improve their health through scientific dietary adjustments. I hope this article can bring hope and practical help to more diabetes patients.

Can pancreatic β-cells regenerate?

In our pancreas, there is an important group of “workers”—insulin β-cells. They are responsible for producing insulin, a hormone crucial for regulating blood sugar levels. Imagine insulin as a key that helps glucose enter cells, providing energy for the body. However, when β-cells are damaged or dysfunctional, this key fails, and diabetes strikes.

β-cells are specialized cells located in the islets of Langerhans (also known as islets) in the pancreas. In type 1 diabetes, the immune system mistakenly attacks and destroys β-cells, leading to little or no insulin production. In type 2 diabetes, due to prolonged insulin resistance and consequent overwork, β-cells often become dysfunctional, ultimately leading to their failure and even apoptosis.

Despite these challenges, β-cells do have limited regenerative and reparative abilities, especially under appropriate conditions. This regenerative ability diminishes with age and diabetes progression but is not completely lost. By reducing the metabolic stress on these cells and creating a conducive environment for their recovery, their function can be enhanced and, in some cases, they can regenerate. Numerous studies have found that the β-cell function in humans can significantly improve in as little as a week (Zhyzhneuskaya et al., 2020 & Meier & Bonadonna, 2013).

Why conventional treatments rarely see β-cell regeneration?

You may ask why we seldom see β-cell repair or regeneration under conventional guidance. Many people, including some medical professionals, have no hope for this. My colleagues at the Go Wise Life Team and I believe this is closely related to the usual treatment methods and dietary habits.

Limitations of medication:

Many medical professionals today still believe that type 2 diabetes is caused by a lack of insulin or, more precisely, a relative lack of insulin. However, this view may not be correct. If the treatment of diabetes focuses on this direction, it may only focus on controlling symptoms while continuing to exacerbate the insulin resistance underlying type 2 diabetes. If you are interested, you can watch another video program on our website, “Dr. Bikman: From Health to Diabetes—What Triggered This Switch?” Many diabetes medications increase insulin secretion, but this does not help β-cell recovery. On the contrary, many researchers believe that insulin secretagogues make β-cells work harder, which may lead to their exhaustion and even depletion over time (Costes et al., 2013; Eizirik et al., 2008).

Impact of traditional high-carbohydrate diets:

Due to dietary beliefs and medication reasons, traditional diabetes dietary recommendations often include large amounts of carbohydrates (or significant portions of carbohydrate dietary recommendations, sometimes combined with a strategy of eating smaller, more frequent meals). Apart from dietary cultural factors, consuming carbohydrates while on medication can actually prevent hypoglycemic events during medication. Remember those movie scenes where type 2 diabetes patients suddenly experience hypoglycemia, and people give them sugar? This is necessary in emergencies. But the problem is, all this might not need to happen.

In a sense, it’s like giving alcohol to someone with alcohol addiction during a craving; this can control the current situation (the body feels much better immediately), but the addiction continues to worsen. If interested, you can listen to Dr. Jason Fung from Canada in “Reversing Diabetes, Starting Anew”. This high-carbohydrate dietary pattern leads to frequent blood sugar fluctuations, increasing the burden on β-cells. When patients’ blood sugar levels are elevated and regulated with medication or exogenous insulin, they are asked to consume carbohydrates to prevent hypoglycemia, creating a “vicious cycle.” Long-term high carbohydrate intake also promotes chronic inflammation throughout the body, further damaging β-cells (Antunes et al., 2020; Karimi et al., 2021).

Can dietary adjustments help β-cells recover?

Although this may vary from person to person, research shows it is entirely possible. We believe diet plays a decisive role in diabetes remission and management and can significantly impact β-cell health. By choosing the right dietary strategies, diabetes patients can reduce insulin requirements, improve blood sugar control, and potentially aid β-cell recovery. Two main dietary methods show promise in this regard: low-carbohydrate diets and intermittent fasting or caloric restriction (Feinman et al., 2015; Longo & Mattson, 2014; Taylor, 2016).

【Low-Carbohydrate Diet】

A low-carbohydrate diet (LCD) focuses on reducing carbohydrate intake, which is broken down into glucose and can cause drastic blood sugar fluctuations. By reducing carbohydrate intake, these diets help lower blood sugar levels and reduce the amount of insulin needed. In very low carbohydrate diet (VLCD) patterns, insulin secretion is very low, making β-cell workload very light.

Benefits of a low-carbohydrate diet:

- Improved blood sugar control: Lowering carbohydrate intake helps stabilize blood sugar levels and reduces the risk of hyperglycemia and its related complications.

- Reduced insulin demand: With fewer carbohydrates to process, the pancreas needs to produce less insulin, potentially allowing β-cells to rest and recover, which is key to their restoration if possible.

- Weight loss: Low-carbohydrate diets often lead to weight loss (mainly fat loss, not lean tissue), which can improve insulin sensitivity and further reduce the burden on β-cells.

【Intermittent Fasting and Caloric Restriction】

Intermittent fasting (IF) and caloric restriction involve periodically reducing food intake to improve metabolic health. These methods can enhance insulin sensitivity, reduce inflammation, and promote cellular repair processes like autophagy.

Benefits of intermittent fasting and caloric restriction:

- Improved insulin sensitivity: Fasting periods help the body become more sensitive to insulin, reducing the overall need for insulin production.

- Reduced glucose toxicity: Lower blood sugar levels reduce the toxic effects of high glucose on β-cells, potentially aiding their recovery.

- Enhanced autophagy: Fasting stimulates autophagy, a cellular process that removes damaged components, helping maintain β-cell health.

Case Study:

Changes in Elderly Type 2 Diabetes Patients with Low-Carbohydrate and Intermittent Fasting Diets Let me share an inspiring case. This patient is a 77-year-old lady who has been “fighting” type 2 diabetes for 18 years. With limited results from traditional treatments, she decided to try a new dietary strategy: a low-carbohydrate diet combined with intermittent fasting, similar to the 16/8 pattern.

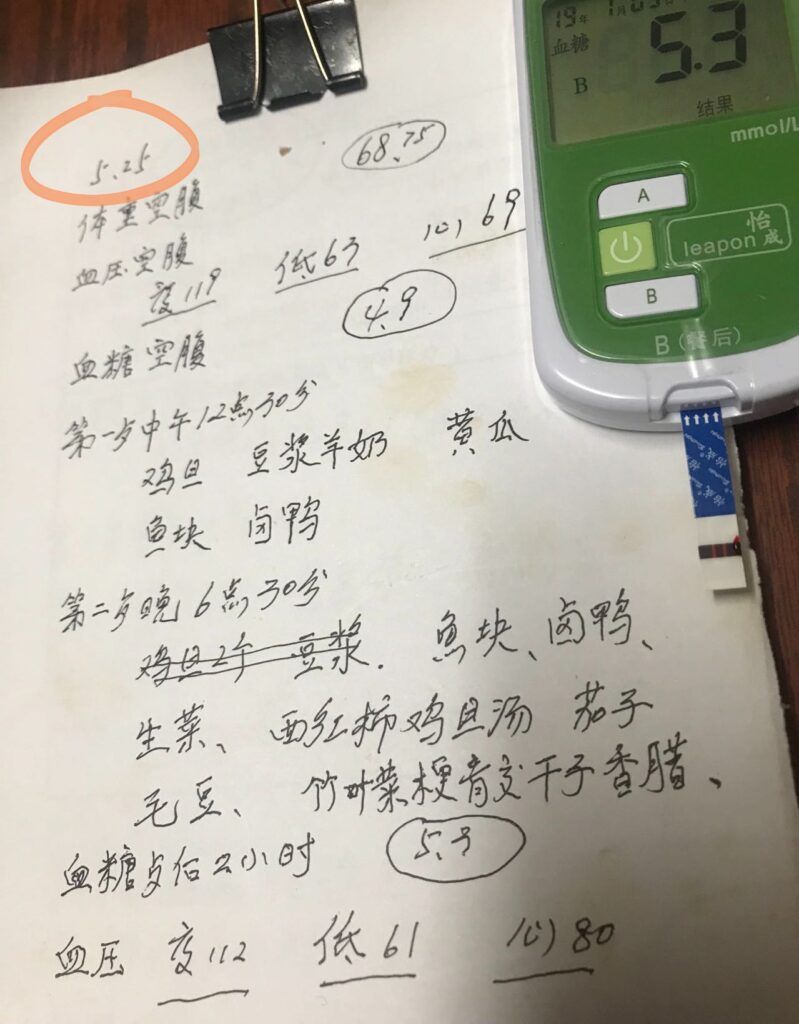

This lady had an 8-hour eating window daily, typically from noon to 8 PM. Her diet mainly consisted of non-starchy vegetables, healthy fats, and quality protein, with strict carbohydrate restriction. After six months, her fasting blood sugar dropped to around 5 mmol/L, and her postprandial blood sugar stabilized between 5 and 6 mmol/L. Even when she occasionally ate high-carbohydrate foods, her blood sugar quickly returned to baseline levels. Over the past six months, her life has changed significantly. She summarized her changes as follows:

- Her weight dropped from over 160 pounds to 140 pounds, her waist reduced from 36 inches to 30 inches, and walking became easier.

- With the doctor’s approval, her diabetes medication was gradually reduced, and now she doesn’t take any medication. Monitoring blood sugar after breakfast and dinner, her fasting blood sugar remains around 5, and postprandial blood sugar around 6, returning to 5 after 2 hours, very stable.

- Her blood pressure is gradually decreasing, monitored morning and night, maintaining a systolic pressure of 130-140 and diastolic pressure of 60-70 in the morning, and 120-130/50-60 in the evening.

- She eats only two meals a day, from 12:00 PM to 7:00 PM, eating each meal to fullness without calorie restriction, feeling no hunger, with ample energy, normal memory and reaction ability, and normal sleep.

Aunt Mei shared her data on May 25, 2024. Fasting Glucose level was 4.9 mmol/L. Postprandial blood glucose level is 5.9 mmol/L. Want to know her story? Click here.

How did she achieve this? Here are the dietary suggestions our team provided, for your reference.

Recommendations for Implementing a Low-Carbohydrate Diet:

- Limit carbohydrate intake: Restrict daily carbohydrates to below 50 grams, avoiding high-refined sugar and starchy foods like white bread, pastries, and sugary drinks.

- Eat more non-starchy vegetables: Such as leafy greens, cauliflower, broccoli, which are not only low in carbohydrates but also rich in fiber and nutrients.

- Choose healthy fats: Such as avocados, nuts, and olive oil, which help with satiety and cardiovascular health.

- Quality protein: Chicken, fish, tofu, etc., are good protein sources to help maintain muscle mass.

- No calorie restriction during meals.

Recommendations for Implementing Intermittent Fasting:

- Start with a relaxed fasting regimen: Gradually reduce from three meals a day to two meals, narrowing the eating window to within 8 hours.

- Stay hydrated: Drink plenty of water, tea, or other non-caloric beverages during fasting periods.

- Balanced diet during eating windows: Even with intermittent fasting, ensure balanced nutrition.

Our Observations and Summary

For many friends with type 2 diabetes and those with prediabetes, combining a low-carb diet with intermittent fasting can yield better results. This approach not only helps with blood sugar control but also significantly reduces the burden on β-cells, promoting their recovery and regeneration.

Although many people disagree with the above strategy (whether they don’t believe in the clinical evidence behind it or think that culturally, Chinese people won’t accept such a counter-traditional diet), we believe this is related to unscientific practices and various interfering factors during implementation.

A plan confirmed by extensive clinical research does not naturally work in real life. The reason is that diabetes patients face complex daily environments, which are entirely different from being “locked” in a hospital ward for treatment. This involves psychological, cultural, cognitive, economic, social, and family support factors, as well as the most critical factor—how determined one is to make a change that may bring long-term benefits but could cause short-term “suffering.”

Below are some key factors for success we have summarized from practical cases:

- Consult Professionals: Before making any significant dietary changes, consult with doctors experienced in low-carb ketogenic treatment and registered dietitians with practical experience to ensure safety and suitability.

- Monitor Blood Sugar Levels: Regularly monitor blood sugar to assess the effects of dietary changes and make necessary adjustments. Simply put, if patients use a 24-hour continuous glucose monitor, the effect will be significantly enhanced and may even be decisive.

- Stay Patient: Recovery of β-cells is a gradual process. Stick to scientific dietary adjustments and give your body time to adapt and recover. If you find your ability to handle carbohydrates improving, this might be a good sign. This does not necessarily mean that β-cells are regrowing, but at least it shows they are not suffering as much as before. Do not rush; this takes time.

- Get Support: If possible, join offline support groups for regular exchanges and professional assistance. In the absence of offline support, it is best to join online support groups, professional reversal camps, or online communities to share experiences, gain motivation, and receive advice. The internet has a plethora of information that often conflicts, requiring a certain level of analytical and judgment skills. Learning on one’s own may only be suitable for some, while many need assistance.

Facing Voices of Doubt

Voices of doubt are necessary. We have found that, in many cases, when people first learn about low-carb diets, intermittent fasting, or calorie-restricted diets, they associate them with cult-like activities seen in movies or consider them extreme behaviors. Facing doubt, we know how to communicate rationally: with scientific literature, clinical evidence, and our statistically significant case study results.

A low-carb diet can reduce blood sugar in a short time and give the pancreas a valuable rest. Does this mean practitioners need to do this for life? We believe this is not necessary, nor is it the goal of dietary intervention. The ultimate goal is to re-establish metabolic flexibility. Therefore, we advocate gradually restoring carbohydrates after a strict low-carb intervention period until reaching a level of carbohydrate tolerance suitable for oneself and can be sustained long-term.

If this day comes, do you think this is proof of β-cell recovery or even regeneration? Feel free to leave your opinions and insights.

Conclusion

Although managing and treating diabetes is challenging, restoring insulin β-cell function through scientific dietary strategies is not an impossible task. Low-carb diets and intermittent fasting are two effective methods that can improve blood sugar, reduce the burden on β-cells, and promote their recovery and regeneration. We hope this article brings you new ideas and hope, and together, let’s move towards a healthier life.

For Chinese version? Click here.

Special Notes and Author’s Disclosure

The author of this article has experience with low-carb diets and may have a preference for low-carb diets. Readers should objectively, rationally, and critically read this article to gain their independent views. If you have any suggestions or opinions, please contact us at: gowiselife@126.com. We welcome discussion and correction.

The author of this article is the co-founder and director of the “Go Wise Life – 21-Day Low-Carb Nutrition Reversal Camp” and will benefit from the operation of the reversal camp.

Reference

Meier, J. J., & Bonadonna, R. C. (2013). Role of Reduced β-Cell Mass Versus Impaired β-Cell Function in the Pathogenesis of Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care, 36(Supplement_2), S113–S119. https://doi.org/10.2337/dcS13-2008

Zhyzhneuskaya, S. V., Al-Mrabeh, A., Peters, C., Barnes, A., Aribisala, B., Hollingsworth, K. G., McConnachie, A., Sattar, N., Lean, M. E. J., & Taylor, R. (2020). Time Course of Normalization of Functional β-Cell Capacity in the Diabetes Remission Clinical Trial After Weight Loss in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care, 43(4), 813–820. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc19-0371

Feinman RD, Pogozelski WK, Astrup A, et al. Dietary carbohydrate restriction as the first approach in diabetes management: Critical review and evidence base. Nutrition. 2015;31(1):1-13. DOI: 10.1016/j.nut.2014.06.011

Longo, V. D., & Mattson, M. P. (2014). Fasting: molecular mechanisms and clinical applications. Cell metabolism, 19(2), 181–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2013.12.008

Taylor R. (2016). Calorie restriction and reversal of type 2 diabetes. Expert review of endocrinology & metabolism, 11(6), 521–528. https://doi.org/10.1080/17446651.2016.1239525

Costes, S., Langen, R., Gurlo, T., Matveyenko, A. V., & Butler, P. C. (2013). β-Cell failure in type 2 diabetes: a case of asking too much of too few?. Diabetes, 62(2), 327–335. https://doi.org/10.2337/db12-1326。文中提到,随着胰岛素抵抗的增加,一些个体的β细胞适应性会降低,导致IAPP和胰岛素的折叠和处理负担增加,可能会超过某些β细胞的阈值。在这些β细胞中,积累的有毒寡聚体会影响β细胞的功能和生存能力,最终导致β细胞功能和数量的逐渐丧失

Eizirik, D. L., Cardozo, A. K., & Cnop, M. (2008). The Role for Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Diabetes Mellitus. Endocrine Reviews, 29(1), 42–61. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2007-0015。文中提到胰岛β细胞在面对持续增加的胰岛素合成和分泌需求时,会面临着巨大的挑战。随着时间的推移,由于胰岛素分子的轻微变化可能导致蛋白质的错误折叠,从而诱发ER压力、β细胞功能障碍和死亡,最终可能导致糖尿病的发生。

Antunes, M. M., Godoy, G., de Almeida-Souza, C. B., da Rocha, B. A., da Silva-Santi, L. G., Masi, L. N., Carbonera, F., Visentainer, J. V., Curi, R., & Bazotte, R. B. (2020). A high-carbohydrate diet induces greater inflammation than a high-fat diet in mouse skeletal muscle. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research, 53, e9039. https://doi.org/10.1590/1414-431X20199039

Karimi, E., Yarizadeh, H., Setayesh, L., Sajjadi, S. F., Ghodoosi, N., Khorraminezhad, L., & Mirzaei, K. (2021). High carbohydrate intakes may predict more inflammatory status than high fat intakes in pre-menopause women with overweight or obesity: A cross-sectional study. BMC Research Notes, 14(1), 279. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-021-05699-1